Author’s Gab, Reader Talk.

A letter to you, the reader, so that you can finally figure out what I’m thinking.

—————————————

This Month: Technical prowess in poetry

————————————————–

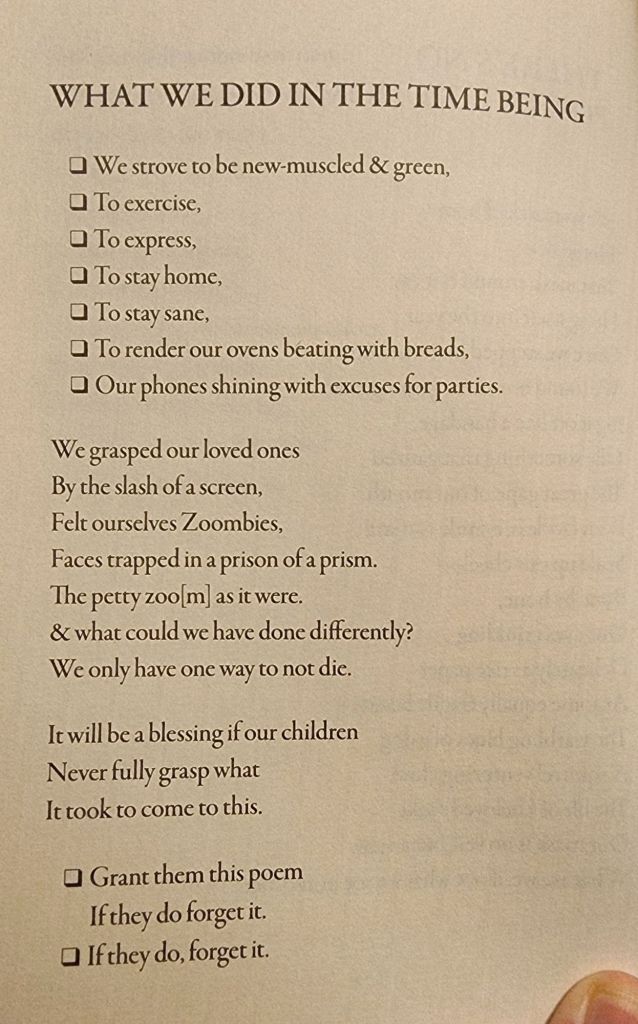

The above poems are by Amanda Gorman from her book, “Call Us What We Carry”. They are a few examples of technical prowess when it is used in poetry.

“Technical prowess in poetry is mostly evident when you are not aware of it. So when I am undisturbed by the way a poem looks on the page and sounds in the inner ear, it probably means that the poet’s grasp of the nuts and bolts of making poetry is firm.

— readingdarling on Instagram

If I am not left wondering about peculiarities of spacing, line length and breaks, unsupportive punctuation and so on, then I am free to simply read. And if then, I read and experience poems like a wash or rush, like an immersion, or an engulfment, even through what might be obscure or not immediately decipherable, I am an easy convert to the poet’s interests.

If, on top of that, I sense behind the poetic subjects and the individual poems, a mind alive to all questions, a mind that won’t allow itself to be stupefied by fashionable obsessions and worthiness flexes, and that won’t express itself in lazy cliche, then I will return and return.”

Dear Reader,

I started out this month thinking about technicality in poetry all wrong. I was thinking about it like a head and heart thing, where it’s the emotion that drives a poem instead of getting all in your head and overthinking it. But, the more I think about technicality in poetry, and using it effectively, I realize that is actually not what I’m trying to say at all. This is because technicality is in the essence of poetry. It’s what makes a poem a poem. It’s the box we are all trying to squeeze in or squeeze out of when we write poetry. Whether we like that box or not, it’s still there. I think, it’s how we use it this is the thing that is so masterful, that imbues a poem with so much meaning — or, it can completely wreck it. That means technical prowess, the knowledge of how to use technicality, is an art we all must learn.

“The study of the nature, forms, rules, and techniques is called poetics; part of this, the study of poetic meter and sound, is called prosody. The following poetics describes very well the majority of poems written in English from the late 15th century (the time just before Shakespeare) to the present. The major exception is free verse, which is primarily a 20th-century phenomenon.”

— Alan Lindsay and Candace Bergstrom, “An Introduction to Poetry”, from Chapter 7, “The Technical Language of Poetry”

When I was a lot younger, I used to overthink the technicality in my poetry… and try to escape it altogether by writing free verse. But, as I have stated, overthinking technicality is an easy death trap to fall into. Many times, I have ensnared myself there by putting something in a poem to try to emphasize something that isn’t obvious to the reader; so, the meaning gets lost.

An example of this is a poem someone asked me to review for them earlier this month, because they were submitting it for a scholarship. I did really enjoy the poem, because the writer expressed a struggle with perfectionism and the need to be human, much like Isabela Madrigal struggles with it in the movie, Encanto. The poem was written in free verse, but it had all these capitals everywhere in it. So, I asked about it. It turns out, all the capitalized words in the poem were contranyms, a single word that possesses two contradictory or opposite meanings, where the specific meaning is determined by the context of its use. You never would have known that without the explanation, though. The meaning would be lost on the reader and all they would know is that those capitals were distracting. I suggested adding that explanation to the poem in its current state and emphasizing the core themes of the struggle with perfectionism, which I felt was the heart of the poem.

But afterwards, it ignited something in me. It’s not just because I honestly enjoy helping people with their writing. It’s because it reminded me that I used to do that. Even when I wrote “Stars”, my debut semi-perfect sonnet in college, published in Parnassus, Taylor’s literary journal, I put capitals at the beginning of each subsequent line to represent the seven main spectral types of stars, a technical detail I’m sure almost certainly comes across as a hidden code in the poem, thinking about it years later. An abrupt capital is something that will cause the reader to stop for sure, but overuse or hidden meaning always demands an explanation. Good explanations also exist, like Emily Dickenson’s personification of death in her poem, “Because I could not stop for Death” and E.E. Cummings’ “[Buffalo Bill ‘s]”, which uses capitals to create emphasis and draw attention to his pronouns at critical junctures within the poem.

Likewise, writing free verse actually demands from us more technicality than if we had chosen another form. “While some contemporary poets who write in free verse also dabble in traditional forms, these same poets do not believe that free verse is without formal requirements,” (Clark, 121). We cannot entertain the idea, as we often seem to, that free verse is escapism. It sets us free to create poems at our own whims, craft our own vices and damn form and technicality altogether, right? Wrong! The ghost of form and technicality still lurks in the background. It’s just now, we writers are making the box it fits in. And, it is then up to us to utilize that box effectively with what we have learned. This is something else I have learned over the years.

In my spare time, I have been reading Amanda Gorman’s “Call Us What We Carry”. And, I will tell you: while many of her poems are in free verse, she has a strong grip on technicality and form. Her ingenious lies in not just her discussion of American race and politics, COVID-19 and other themes she is said to explore in the book, such as, according to Google: “grief, historical reckoning, collective and individual identity and hope in the face of struggle.” It also lies in how she presents those topics in her poetry. I was particularly struck by three of them: “Please”, “What We Did in the Time Being” and “Essex 1”. “Please” and “Essex 1” are part of the section in the book entitled “Requiem” and “Essex 1” is the opener to the section, “What a Piece of Wreck is Man”.

“The first set of lyrics in what feels like a mournful song arrive as part of Requiem in a vertically formatted, three-line poem titled “Please,” which has 12 words separated by the page equivalent of six feet of distance using brackets. The reader is required to change their perspective or reorient the page to determine the many meanings of the words on the page, along with the act of shifting a traditional reading style.”

— Joshunda Sanders, from the article, “Amanda Gorman’s Poetry Collection Call Us What We Carry Is Finally Here” in Oprah Daily

Gorman uses the technical style of this poem to deliberately force us to stop and think about the poem itself. This is accomplished not only by orientation but by the brackets that break up the chain of thought within the poem. It’s as if the poem is saying to us, “Stop and insert your thought here.” It’s a device that asks us to be deliberate with our thoughts and with the meaning of the poem itself. The poem is only two lines, but it’s two lines that matter. This is definitely a sound example of literacy in technicality because, without the poem’s technicality, it LOSES its meaning. It is not lost on the reader in the first place.

I hate to get that punchy, but Gormon doesn’t stop there. She punches us with her list poem, “What We Did in the Time Being”. List poems do “what the title suggests: In one line after another, it offers a new direct description, metaphor or simile. Because the list poem is not proceeding conventionally through a typical plot or into the interior life of a protagonist, the challenge is to make each of the lines intriguing units of poetry.” It’s a list integrated with lines of free verse that speaks about the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic and asks us to remember that time. The way the poem is presented is like a time capsule. Even if you don’t get it right away and need the context that it’s about COVID-19, the dynamic list she makes is going to tell you to pay attention and not forget. She doesn’t need to say it because of the way the poem is structured, but she does anyway:

-

“Grant them this poem

If they do forget it. -

If they do, forget it.”

In Essex 1, however, the meaning isn’t so intrinsic, so that forces an explanation. The poem is shaped like a gigantic fish, which we later discover is a whale, because she explains:

“The Essex 1 was an American whaling ship that was attacked by a sperm whale in 1820. Of the twenty crewmen, only eight were rescued after being stranded at sea for three months. The tragedy inspired Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. At the time, whales were killed for blubber, which was used in oil lamps and other commodities.”

— Gorman, “Essex 1”, on pages 32 and 33 in her book, “Call Us What We Carry”

Then, she quotes Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: “I’m not telling you a story so much as a shipwreck — the pieces floating, finally legible. This provides context for the poem that comes next, for which you actually have to turn the book to read. And, as much as there is punctuation in the poem, what we are seeing is a mashing together of words in almost a stream of consciousness that doesn’t break until the spaces in the fish’s tail. Thus, the reader draws meaning, not simply from the poem’s technicality, but from the context which the poem is placed, which is also a device. This is the method I suggested earlier and one I use myself when I post quotes with my poetry. The set-up and the context convey the meaning.

And so, we have one poem that uses its technicality in free verse to embody meaning, one that uses technicality to intrinsically create meaning and one that uses context to convey the meaning. If you navigate all three, you can see the Gorman utilizes technicality in her free verse to craft forms based on topic that convey her message. Technicality is not an escape for her — it’s strategically placed leverage. She is not free of constraint necessarily but instead uses it to her advantage. More importantly, by doing so, she demonstrates technical prowess, the ability to navigate technicality effortlessly through what she has learned about poetry and use it in an effective manner.

One Instagram user put the concept of technical prowess in poetry like this:

“Technical prowess in poetry is mostly evident when you are not aware of it. So when I am undisturbed by the way a poem looks on the page and sounds in the inner ear, it probably means that the poet’s grasp of the nuts and bolts of making poetry is firm.

If I am not left wondering about peculiarities of spacing, line length and breaks, unsupportive punctuation and so on, then I am free to simply read. And if then, I read and experience poems like a wash or rush, like an immersion, or an engulfment, even through what might be obscure or not immediately decipherable, I am an easy convert to the poet’s interests.

If, on top of that, I sense behind the poetic subjects and the individual poems, a mind alive to all questions, a mind that won’t allow itself to be stupefied by fashionable obsessions and worthiness flexes, and that won’t express itself in lazy cliche, then I will return and return.”

— @readingdarling on Instagram

I think that means that, if we are to approach technicality correctly, we need to make a poem’s meaning obvious at first glance. Likewise, we can’t flee from poetic forms and creating our own structures to convey meaning in free verse. Instead, as writers, we have to be so fluid in the language of poetry that writing it, a well as reading it, is like breathing. With one breath, we get it. With one exhale, we remember it. Like, if you steer the ship right without overthinking or any hidden paths your reader might get hung up on or really think about what this form is trying to say to you, you may just succeed in conveying what you are trying to convey, much like Gorman did in her poems.

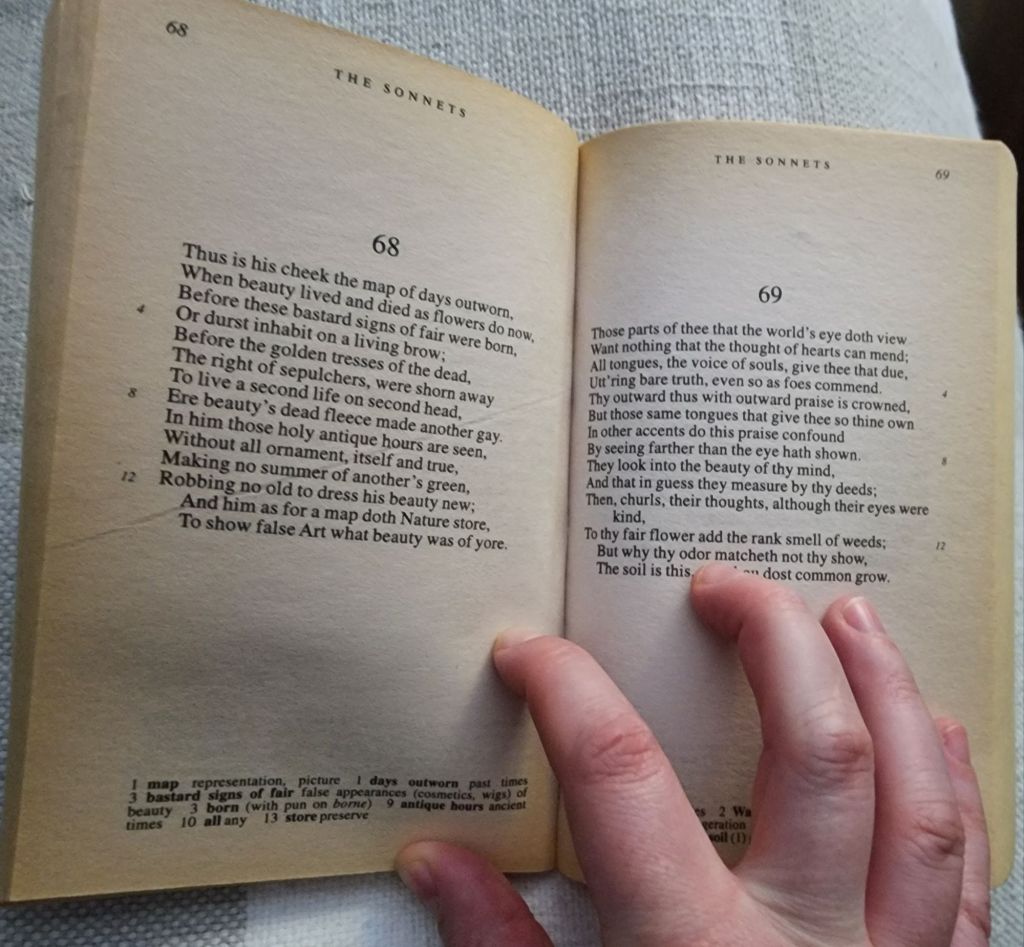

I have, for a long time, been working on a collection of poetry, most of which is published on this website, which focuses on form. I recently went nuts and wrote poem after poem in one weekend, righteously inspired to chase after my own work after helping that one person I mentioned, some of which I have recently published and some which I have not yet for various reasons. I have also gone back and edited old poems, seeking consistency in my collection. I’m currently in the middle of writing an English sonnet called, “How to Write a Sonnet”, a fun poke at what it takes to write the form. But, in checking my meter, I have grown increasingly frustrated. I write a lot of conversational poetry; however, a sonnet is a da-DUM pattern, lending itself to mostly one or two syllable words. It’s worth noting that Shakespeare occasionally breaks the rules, such as in Sonnet 68, where he utilizes the word “sepulchers” to describe the cutting of the hair for a wig of a young man who tragically died an early death:

“Before the golden tresses of the dead,

The right of sepulchers, were shorn away

To live a second life on second head,

Ere beauty’s dead fleece made another gay.”— William Shakespeare, “Sonnet 68”

“Sepulchers” is a three-syllable word that has the emphasis on the first syllable and not the other two. This makes it a trochee in meter, which is basically a no-no in traditional sonnets. Trochees are “metrical (feet) consisting of one long syllable followed by one short syllable or of one stressed syllable followed by one unstressed syllable (as in apple),” (“Trochee”). What you can do with them is you can use them for emphasis, but only when you have grasped the basics. And so, in my attempt to write a textbook sonnet, I have been pulling out my hair trying to get rid of the all the trochees and get it to conform to the meter. This essentially is the bane of writing a conversational poem first and checking to see if it conforms to the form later. Nonetheless, I have found myself muttering under my breath, “Okay, Shakespeare wrote this deathtrap, so…”.

But, you know what it has done for me? Through trial and error, it is re-teaching me how to write a sonnet, forming me to where I can easily traverse the form. I can remember when I wrote my first sonnet, “Crimson”, for English class in high school. My teacher wrote in all red pen at the top of my paper, “THIS IS NOT A SONNET.” Now, I have endeavored to fix it since then. But, my understanding of the form has come a long way since then. I have a better grasp on the technicality of sonnets now than I did then, but it has taken many years for me to craft and hone it.

And, I think, this is ultimately what we need to do in our study of technicality. To become more technically proficient, we need to abandon our arrogance, write “THIS IS NOT A SONNET” on the top of every poem and endeavor to try again and again until we have conveyed what we mean to say without any hiccups. And, dare I say it, this takes practice. This takes study. This takes the time late at night or on a Sunday we don’t think we have. Practice, as they say, breeds proficiency. And, with proficiency, we can prowl around poems like a tiger prowls around their prey before they pounce. We just have to strive towards it.

Think about that. ~

Sincerely, Your Writer,

Jessica A. McLean

Citations:

Clark, Kevin. The Mind’s Eye: A Guide to Writing Poetry. Longman, 2008.

Cummings, E. E. “[Buffalo Bill’s].” Poetry Foundation, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47244/buffalo-bill-s.

Dickinson, Emily. “Because I could not stop for Death — (479).” Poetry Foundation, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47652/because-i-could-not-stop-for-death-479.

Gorman, Amanda. Call Us What We Carry. Viking, 2021.

Guerrero, Diane, and Stephanie Beatriz, performers. “What Else Can I Do? (From ‘Encanto’) (Audio Only).” YouTube, uploaded by DisneyMusicVEVO, 14 Jan. 2022, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bBeZSuHI4Qc.

Jackson, Mitchell S. “A Review of Amanda Gorman’s Call Us What We Carry.” Oprah Daily, 25 Jan. 2022, http://www.oprahdaily.com/entertainment/books/a38403817/review-amanda-gorman-call-us-what-we-carry/.

Lindsay, Alan, and Candace Bergstrom. “Chapter 7: The Technical Language of Poetry”. An Introduction to Poetry. Pressbooks. 2019. pressbooks.pub/introtopoetry2019/chapter/chapter-7-the-technical-language-of-poetry/.

Shakespeare, William. “Sonnet 68.” Shakespeare’s Sonnets, edited by Barbara A. Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles, Folger Shakespeare Library, n.d., http://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/shakespeares-sonnets/read/68/.

Shakespeare, William. The Sonnets. Edited by William Burto, with an introduction by W. H. Auden, Signet Classic, 1988.

“Technical Features of Poetry.” Poetry: A Beginner’s Guide, Kinnu.xyz, kinnu.xyz/kinnuverse/culture/poetry-a-beginners-guide/technical-features-of-poetry/. Accessed 3 Oct. 2025 []. You can find more information on Kinnu.xyz.

“Trochee.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trochee.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Recent Happenings:

- Recent Ad-Lib Activity:

- Sepetember 2025 Ad Lib is here

- TBA: I’m working on finishing my series on form. Stay tuned.

- Sepetember 2025 Ad Lib is here

- Recently Published:

- Poems Added:

- Semi-perfect sonnet, “Grandstanding”

- Etheree, “Double rainbow”

- Etheree, “Low Battery”

- Poems Added:

- Editing, editing, and more editing.

- Waiting

……………………………………………………………………………………………………..